The Drama Triangle, Relational Dysfunction, and Uncontrolling Love

By Shane Moe

The drama triangle’s dysfunctional Persecutor, Victim, and Rescuer roles create systemically self-perpetuating psychosocial problems that uncontrolling love avoids and helps heal.

After one of my clients, who struggled with overwhelming levels of chronic shame and anxiety, tearfully described the highly critical, controlling, and rigidly conservative Christian family in which he was raised, I remember saying to him, “Yeah, your family wasn’t a support system—it was a suppression system.” He nodded in agreement, with a softened facial expression and attending exhale that conveyed a sense of feeling seen and validated.

On another occasion, when I was seeing a couple for marital therapy, they began locking horns in a bitter disagreement during one of our early sessions. Each was trying to forcefully change the other’s perceptions through verbal jousting and volume. I interrupted them and asked, “What’s more important to you right now—the relationship or being right?” They both sat quietly, reflecting on how they had been going about the interaction, and eventually resumed their exchange with less defensiveness and emotional charge.

On yet another occasion, one of my clients, who was struggling with complex trauma born out of years of spousal abuse, told me she had thought of her previous therapist as the “captain” of her proverbial ship and that she was hoping I could be the same. I responded by saying, “Actually, I don’t want to be your captain. I want to support you being the captain of your ship.” She sat silently, maintaining steady eye contact and appearing perplexed, but also intrigued to hear more.

These brief anecdotes highlight some of the relational dynamics that therapists routinely hear about and encounter in our work with our clients. In what follows, I’m going to use one particularly helpful and more systemic framework to describe some of the ways in which relationships (and families, churches, or other social/relational systems) characterized by interpersonal control become significantly problematic. At the same time, I’m going to note how these dynamics and their destructive consequences contrast with those of uncontrolling love.

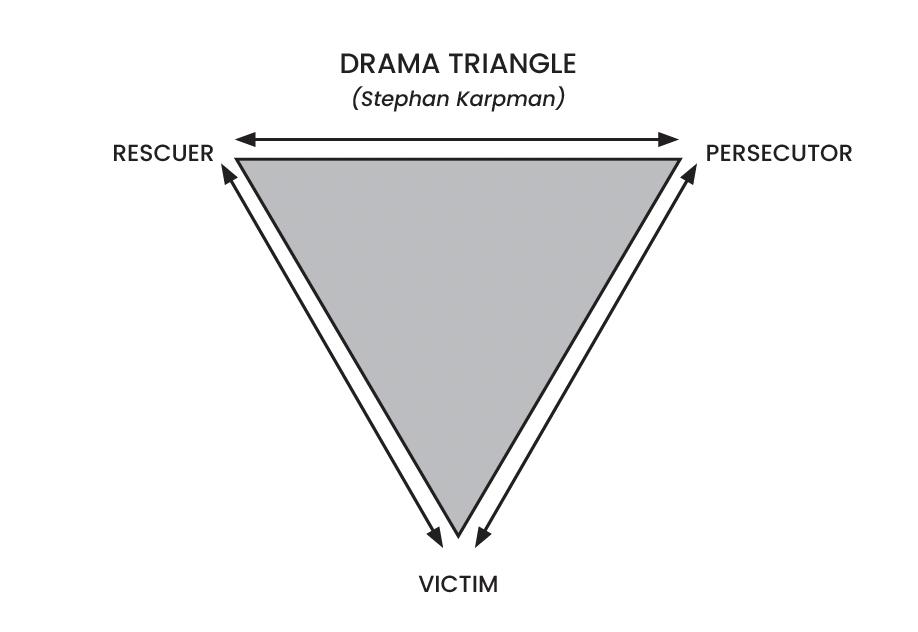

Psychiatry professor and clinician Stephen Karpman’s famous drama triangle is a tool therapists sometimes use to discuss the problematic roles and relational positions people often take in unhealthy relationships or social systems characterized by destructive relational dynamics (whether families, churches, schools, companies, governments, societies, or otherwise). Persecutors irresponsibly attack, blame, control, and otherwise oppress or abuse others—whether verbally, psychologically, spiritually, emotionally, financially, physically, sexually, or otherwise. Victims irresponsibly “play the victim” to avoid having to take responsibility for themselves, typically by feigning helplessness, complaining about how unfair everything is, or expecting others (and frequently guilting them) to rescue them from the consequences of their actions or inactions. They invoke an irresponsible victim mentality, which we need to distinguish from the reality of being a victim or of having been victimized by a Persecutor, an injustice for which the victim is not responsible and about which they may have to critically speak up or speak out in order to effectively address (rather than reinforce and systemically help perpetuate) the injustice.

Rescuers then—often as a result of thin emotional boundaries, a desire to make themselves feel better, a grandiose sense of superiority, or to avoid taking responsibility for their own issues—over-responsibly seek to shelter, take over for, or otherwise rescue a perceived Victim, ultimately serving to enable and reinforce the latter’s irresponsibility/under-responsibility and maintain that person’s unhealthy dependence upon them (along with any enmeshment and codependency in the relationship). And while such rescuing often looks a lot like love and gets easily mistaken for it—to say nothing of often awarded hero or martyr status—it does not actually operate in the beloved’s best interests and is, instead, born out of the Rescuer’s own psychosocial deficits and discomfort.

The nature of the drama triangle (sometimes called the “VPR Triangle”) is such that those who are caught up in its toxic “dance” tend to just rotate amongst the triangle’s problematic roles or positions, ultimately serving to circulate, sustain, and amplify the system’s dysfunction (be it a family, church, company, or otherwise). Persecutors, for example, often rotate to playing the Victim when being held accountable for or suffering from the negative consequences of their persecutory behaviors, or to the role of Rescuer when wanting to distract from or make up for those irresponsible behaviors. Rescuers often rotate to the position of Persecutor in their impulsive attempts to rescue others, or into the role of Victim themselves when their attempts to rescue someone fail or are not sufficiently appreciated. And those playing the Victim role often rotate to the position of Persecutor through a responsibility-avoiding litany of harsh complaints about others, if not to the role of someone’s Rescuer to feel a compensatory sense of power, relief, or self-worth.

When we examine them more closely, we find that, contrary to the characteristics of uncontrolling love delineated in 1 Corinthians 13:4-7 (as well as the fruit of the Spirit in Galatians 5:22-23 and characteristics of divine wisdom in James 3:13-18), the drama triangle’s problematic roles and relational dynamics routinely traffic in both overt and covert patterns of interpersonal control that lead to significantly problematic natural consequences which then feed back into the relational system and serve to further perpetuate those corrosive control-based dynamics. For example, where loving someone in an uncontrolling way is more likely to promote feelings of self-acceptance or self-worth, of calm or safety, and of a sense of healthy agency or empowerment in others, the drama triangle’s dynamics of interpersonal control, even when engaged in by seemingly well-intentioned Rescuers, routinely contribute to significant levels of shame, anxiety, and anger in the parties involved. Reciprocally, then, these distressing feelings often serve to fuel people’s compulsion to control and further engage in the triangle’s various roles. In cases of a Perpetrator’s more severe or chronic abuses, of course, their entitlement-driven efforts to exert power and control over others often contribute to full-blown post-traumatic stress or complex trauma in their victims, or in some cases even to their own moral injury (i.e., severe psychological torment over how one has harmed others), all of which contribute to both them and their victims being more vulnerable to further engagement in the triangle’s problematic roles. Uncontrolling love, on the other hand, is neither driven by fear and anxiety nor abuses and traumatizes the beloved. In fact, it helps people better manage all of these difficult emotions and heal from the interpersonal abuse and trauma that have so often contributed to them.

In addition, whereas uncontrolling love evidences a healthy humility and non-defensiveness, the drama triangle’s roles and control-based dynamics are routinely born out of—as well as serve to fuel, reinforce, and increasingly rigidify—people’s pride and related psychosocial defenses (e.g., denial, suppression, rationalization, projection, displacement, compensation, idealization, and so on). Defense mechanisms, sometimes called ego defenses, are generally psychological processes (typically born out of fear and shame) that conveniently serve to insulate someone from having to face, feel, and deal with their own vulnerable emotions or problematic behaviors. And of course, where you find unhealthy pride, psychosocial defense mechanisms, and strong (often blinding) emotions—you commonly find intellectual rigidity and a lack of, or significant deficits in, self-awareness. By contrast, the humble, non-defensive, and flexible nature of uncontrolling love is more conducive to healthy self-awareness and psychological (both intellectual and emotional) flexibility which, in turn, further helps one love others in uncontrolling ways.

Along with the emotional fallout, unhealthy pride, and problematic psychosocial/ego defenses just mentioned, the drama triangle’s roles and control-laden relational dynamics commonly contribute to patterns of unhealthy relational dependence (e.g., codependency) and to an increasing psychological dependence upon engaging in those roles, with people becoming increasingly emotionally dependent upon persecuting, rescuing, or being rescued. All of which then feeds back into and further perpetuates those systemic dynamics of interpersonal control.

Uncontrolling love, on the other hand, helps free people from unhealthy psychological and relational dependence, helps enhance a healthy sense of personal agency and self-efficacy, and helps empower others in healthy ways that actually serve their best interests. By contrast, the roles and relational dynamics of the drama triangle—even those of the purportedly magnanimous Rescuer—generally serve to keep people captive in unhealthy psychological and relational dependence, erode any healthy sense of agency or self-efficacy, and in the end serve to disempower rather than healthily empower. All of which fails to really serve anyone’s best interests. In fact, these dynamics can render people increasingly psychologically dependent upon having or exerting power over others—with power effectively becoming one’s “drug of choice.” Uncontrolling love, on the other hand, doesn’t share this corrosive and corrupting emotional attachment to power. Rather than controlling others through the exercise of power over, uncontrolling love exercises power under (as theologian Greg Boyd famously called it), lovingly empowering others in ways that recognize, honor, and invest in their personal agency on behalf of their best interests.

Finally, and intimately connected with each and all of its problematic natural consequences (and reciprocally contributing factors) outlined above, the drama triangle’s control-laden roles and rotations militate against the development or maintenance of healthy psychosocial boundaries and a well-differentiated sense of self. When people lack healthy emotional or interpersonal boundaries, they fail to appropriately differentiate between self and other, to know and respect where one stops and the other starts, and to know what belongs to oneself as properly one’s own responsibility (such as one’s own body, thoughts, feelings, and choices or agency) and what belongs to someone else as properly theirs. Which, of course, makes them ripe for controlling or being controlled. They’re more likely to exhibit what the brilliant family therapists and addiction specialists Claudia Bepko and JoAnn Krestan, in their incisive book The Responsibility Trap, call under-responsibility (a failure to appropriately take responsibility for self and be responsible to others)and over-responsibility (problematically taking responsibility for others and their responsibilities, which typically renders one under-responsible for oneself in certain ways by default). And in keeping with the title of Bepko and Krestan’s book, people often wind up trapped in interlocking, mutually reinforcing, systemically self-perpetuating patterns of both under-responsibility and over-responsibility in their relationships with others (and even in their relationship with themselves). Each role in the triangle is largely characterized by under-responsibility, over-responsibility, or some combination of both, and these problematic distortions of healthy responsibility, like the roles of the triangle that traffic in them, routinely manifest in the destructive dynamics of interpersonal control.

When people lack healthy psychosocial boundaries, or what family therapists sometimes call self-differentiation—namely, the ability to maintain an “I” in the midst of the “We,” to separate one’s thoughts and feelings from those of others, and to hold on to self in the midst of the often psychologically fusing and assimilative forces of togetherness in relationships—they’re more likely to feel the need to control others (or if they can’t control them, then relationally cut off) in order to regulate their own anxiety or other emotions. As one of my colleagues profoundly put it, “We tend to be more selfish in relationships when we don’t bring a self to the relationship.” And where uncontrolling love is self-controlled and promotes self-differentiation by honoring the other’s “otherness,” personal boundaries, and self, the roles and relational dynamics of the drama triangle are so often other-controlling, ultimately serving to dismiss, override, assimilate, or in some other way try to eliminate the other’s otherness, boundaries, or self (engaging in forms of what theologian Miroslav Volf has called exclusion, as opposed to the Christlike embrace that welcomes, accepts, and includes the other in their otherness). Where the triangle’s roles and controlling dynamics (including the often controlling love of the triangle’s Rescuer) serve to prevent self-differentiation, uncontrolling love serves to foster it.

Ultimately, self-differentiation reflects an interpersonal relational ability that is itself intimately related to one’s intrapersonal ability (in one’s relationship with self) to adaptively balance or differentiate between one’s emotional and logical processes, which allows one to effectively manage one’s anxiety in the naturally anxiety-conducive realm of interpersonal relationships, intimacy, and difference.

The majority of my work as a therapist involves helping my clients improve their intrapersonal and interpersonal relational processes, boundaries, and health—and consequently their level of self-differentiation. Their increasing self-differentiation, then, helps them escape from or avoid getting sucked into the destructive roles and rotations of the dreaded drama triangle. When my clients are suffering emotional distress as a consequence of someone else’s engagement in the triangle’s problematic roles, I help them attend to and work through it both intrapersonally and interpersonally. And when my clients themselves are engaging in the poorly self-differentiated patterns of the triangle’s Persecutor, Victim, or Rescuer roles, or any combination thereof, I help them more clearly see what’s happening, help them better understand how it is working against their mental health and relationships, and help them increase their level of self-differentiation, all the while being careful to avoid falling into the triangle’s presumptuous and poorly self-differentiated Rescuer role myself.

How do I do this? Largely by letting uncontrolling love inform and shape my therapeutic relationship and work with my clients. Psychotherapy that is informed and shaped by uncontrolling love not only helps people avoid engaging in or colluding with the drama triangle’s problematic roles and rotations, it also helps them experience healing and freedom from its enslaving and destructive natural consequences. It helps them heal and gain freedom from the shame, anxiety, and anger; from the pride, defensiveness, and rigidity; from the unhealthy relational dependence, disempowerment, and lack of self-efficacy; and from those deficits in one’s psychosocial boundaries and self-differentiation. As noted above, these destructive consequences both result from and systemically feed back into the drama triangle’s problematic, poorly boundaried, and control-saturated relational dynamics, ultimately serving to perpetuate them and sustain so much of what is broken and in need of healing in the human condition.

Uncontrolling love is key to this healing. Where the drama triangle ultimately burdens and enslaves—as they say, in the drama triangle everyone winds up a victim—psychotherapy informed and characterized by uncontrolling love helps unburden and liberate, as well as helps people increasingly exercise uncontrolling love themselves.

Shane Moe is a licensed marriage and family therapist and trauma treatment specialist in private practice in the Twin Cities south metro. He is a certified EMDR clinician with additional specializations in the DBT and IFS models of psychotherapy. He earned a Master of Divinity degree in 2008 and a Master of Arts in Marriage and Family Therapy degree in 2011, both from Bethel University.

To purchase the book from which this essay comes, see Love Does Not Control: Therapists, Psychologists, and Counselors Explore Uncontrolling Love