Open and Relational Theology in a Pluralistic Age

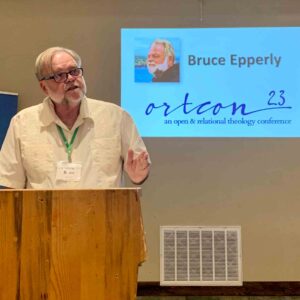

Bruce G. Epperly

Let us begin with a moment of stillness, breathing deeply the Spirit of the Universe, inhaling the divine energy of life, which inspires, heals, and transforms, opening to the wonder of this Holy Here and Now, and inviting us to do something beautiful with our one wild and precious life.

One of my mentors Allan Armstrong Hunter wrote the following Prayer:

I breathe your blue sky deeply in

To blow it gladly back again!

I breathe your shining beauty in

To call forth the buried talent in me.

I breathe your healing energy in

To vibrate through each body cell.

We breathe your reconciling spirit in

To bring peace in us, and in the world.

We breathe your resurrection power in

To make our relationships new and glad.

We breathe your strength and warmth and humor in

To share joyously with all we meet.

(Allan Armstrong Hunter)

In the dialogue Phaedrus, Plato’s Socrates asks the young Athenian, “Where have you come from and where are you going?” The young man initially describes how he’s spent his day. In the course of the conversation, he discovers that Socrates’ question points to something deeper, the nature of our spiritual journeys, our origin as children of the divine and our destiny as lovers of wisdom, whose relationships and values shape our spiritual evolution.

At 70, I am asking myself a similar question, “Where have I come from and where am I going?” in my quest for wholeness and individuation that allows me to face mortality with a sense of calm and generativity, seeking the stature that Bernard Loomer speaks about when he describes spiritual size the primary theological and ethical virtue. In words I first heard 45 years ago in Loomer’s Claremont seminar, sitting alongside Catherine Keller, Rebecca Parker, and Rita Nakashima Brock:

By size I mean the stature of a person’s soul, the range and depth of his love, and his capacity for relationships. I mean the volume of life you can take into your being and still maintain your integrity and individuality, the intensity and variety of outlook you can entertain in the unity of your being without feeling defensive or insecure. I mean the strength of your spirit to encourage others to become freer in the development of their diversity and uniqueness.

For me, spiritual wholeness, or stature, involves claiming the totality of our spiritual journey, and finding a home for the many spiritual paths that brought me to this point, and with that a word of gratitude to one of my teachers John Cobb, from whom the phrase “pluralistic age,” comes. I do not intend to repeat Cobb’s illuminating and life-changing work, Christ in a Pluralistic Age, but the spirit of universal Christ and his vision of creative transformation is hopefully present, and inspiring, to a greater or lesser degree, every word I write and speak.

Today, I will not try as James Weldon Johnson who wrote Lift Every Voice and Sing, in speaking of the African American preachers of his youth to “unscrew the inscrutable” but I will join theology, spirituality, the quest for justice, spiritual practices, ministry and ecclesiology, evangelism, and some old-time hymns in this brief presentation.[1] My approach will be a form of what I have called “theo-spirituality,” joining 1) the concreteness of experience in all its tragic beauty and contrasting and multifarious unity and 2) the mystical vision of reality with my own story and the larger stories within which we live. Theology is lifeless without spirituality and spirituality needs the framework of theology for interpretation and sharing with the larger community. Together theology and spirituality can be firewalls against fascism and hate, and promote healing of persons and the planet, and the soul of our nation.

The title, “The Roundup for God is On” is autobiographical and sets the stage for describing the process and open and relational journey, as it relates to my life as a Christian inter-spiritual pilgrim and a creative response to the spiritual pluralism of our time. The title comes from the theme song of a Baptist revival meeting held in 1962, “The Roundup for God is On,” led by a preacher to the cowboy movie stars and stunt men, Leonard Eilers. I heard this song when I came forward and accepted Jesus as my personal savior:

Put your foot in the stirrup

Climb up on the horse

The roundup for God is on.

(The roundup for God is on…

The roundup for God is on…

Put your foot in the stirrup…

Climb up on the horse

The roundup for God is on.)

The cowboy evangelist, seeking to revive the Baptists of our church – and Baptists need to be revived regularly – and save the lost souls of our small town in the Salinas Valley, twirled his lariat, hoping to rope some sinners for Jesus. That lariat symbolized to him the circle of salvation. Once roped by Jesus, you were in God’s hands, your sins forgiven and bound for heaven. Outside that lariat’s clutches, outside the herd of believers, your soul is lost and hellfire and brimstone are your destination.

I now believe that the circle of salvation is much wider than a soul-winning lariat, and see God’s love and salvation similar to the circle described by St. Bonaventure –

God is a circle (infinite sphere)

Whose center is everywhere

And whose circumference is nowhere –

The circle of salvation represented security and adventure for a nine-year-old Baptist preacher’s kid, who routinely felt Jesus’ nearness and experienced my savior as the one who walked with me and talked with me, and told me I was his own. I am no longer that child, but without that revival, I wouldn’t be here today.

Another hymn of my youth tells perhaps a more inclusive story of faith in a pluralistic age.

Through many dangers, toils, and snares, I have already come.

‘Tis grace has brought me safe thus far, and grace will lead me home.

John Newton’s “Amazing Grace” is a talisman and guidepost for my sixty-one-year spiritual journey since that revival meeting. A journey best described as deep and wide, “a fountain flowing deep and wide” through spiritual trauma when my father was forced to resign from his pastoral position, my departure from the church, and the experience of feeling suffocated whenever I entered a church building, my finding as a teenager insight and inspiration in Transcendentalism, Tolkien, Alan Watts, Carlos Casteneda’s Don Juan, and imaginative mind expansion on the magical mystery tour of the 60s San Francisco Bay Area scene.

While my life has been a series of conversion experiences, the next personal revival, as pivotal as the Roundup for God and the summers of love, was learning Transcendental Meditation at a SIMS ashram in Berkeley, California, in October 1970.

Equipped with my mantra, I found myself returning to church – a theologically open-spirited American Baptist church, at the edge of San Jose State’s campus – where I was welcomed by two pastors, each of whom saw something special in me, one saw a theologian, the other a pastor-social activist. It was at Grace Baptist, the name is no accident, that I discovered process theology in 1972 when I enrolled in a process theology class, along with my pastor John Akers, taught by Richard Keady, a former priest and student of John Cobb’s. I haven’t looked back as providence has guided my path to wider and wider circles of spirituality, theology, and world loyalty in almost 50 years as a theological student, pastor, professor, spiritual teacher, and seminary administrator.

Over these fifty years, I have embodied what it means to be a Christian who embraces inter-spirituality, that is, one who is committed to Christ and to growing in spirituality by affirming and participating in the spiritual practices of other religious traditions: from TM, I was inspired to study Christian mysticism; several years later, I learned Attitudinal Healing, a new age healing process inspired by A Course in Miracles and discovered that the Bible was a book of healing affirmations and stories and not divisive doctrinal edicts; in the 1980s, I learned Reiki healing touch, a form of hands-on and distant healing and became a reiki master over thirty years ago and discovered the healings of Jesus as a living reality touching our lives today. From the Hindu Gandhi, himself an inter-spiritual pilgrim, I learned the importance of non-violent social change, grounded in spiritual practices, which awakened me to what I describe as “prophetic healing.” At each step, the circle widened, the scope of salvation expanded, stature increased, and diversity and pluralism became inspirational. The center is everywhere, right here and now, and the circle is composed of a myriad centers without an outside or outer circumference.

I have discovered, as a sweatshirt worn by Annie DeRolf announces, “God loves me and there’s nothing I can do about it” and also that “God inspires everyone and there’s nothing we can do about it.” While we may stand in the way of inspiration and love by hard-heartedness, ego, love of power, and doctrinal orthodoxy, the “pure-hearted” who embrace the circle of loving inspiration will see the many faces of God reflected in the insights of their own faith tradition and every faithful spiritual journey. They will learn with Rumi that there are a hundred ways to kneel and kiss the ground.

Open and Relational and Process Theology. I promised a bit of autobiography and you’ve heard the words of a few old hymns. Now, let us briefly and directly turn to theology, spirituality, and spiritual practices, the quest for justice, ministry and ecclesiology, and evangelism, recognizing that they are interdependent aspects of the interplay of God’s revealing and inspiring love and human openness and creativity to the graceful circle that centers and encompasses us.

Tom Oord reports a statement a conversation partner made about the scope of open and relational theology: “If God is present to everyone and reveals in an uncontrolling way, we should expect a variety of religions and diverse views of God.” This statement captures the insight articulated by biblical theologian Terry Fretheim: it is more important to ask the question, “What kind of God do believe in?” than “Do you believe in God?” How we view God shapes our ethics, values, economics, and attitudes toward religious pluralism.[2]

The God of much traditional theology is binary, authoritarian, demanding, punitive, all-powerful, and backward looking. This omnipotent God is the equally, and at times gleefully, source of good and evil, salvation and damnation, and divides the world into the chosen and forgotten, the predestined and reprobate. Sinner and saint are alike sinners in the hands of an angry God, dangling above the fires of hell; yet, even though the saints are undeserving and to some degree hateful to God, God arbitrarily chooses them for salvation. Such a God rules by fear and exclusion, and that God’s followers, when given power, rule with the same hard-hearted binary hatred of “otherness,” claiming to love the sinner while hating the sin, but eventually choosing to destroy any sinner who refuses to follow their path. This binary, exclusionary, authoritarian, and punitive God plays a significant role in the culture war politics of the USA. Conflating Jesus and Trump as sources of salvation, they act as if outside of Trump there is no salvation for our nation.

In contrast to this binary, line-drawing, and authoritarian God, inspiring similar behaviors in “his” followers, the God of ever-widening circles, whose love embraces all things, and whose creativity is the fountainhead of our freedom and creativity, births forth otherness and diversity, treasures each soul, and sees each creature as part of God’s own identity, written on the palms of the divine hand. This amipotent and non-binary God, the God whose power is defined by love, seeks wholeness for all persons, and healing for all creation. Nothing is outside the scope of God’s love and salvation. God will be all in all.

Theologically speaking, the amipotent God has a personal relationship with all creation, inspiring as the evangelicals of my childhood to affirm that personal wholeness emerges from an equally personal relationship with God. Yet, God’s personal relationship with creation, part and whole, inspires a democracy and plurality of revelation. Spiritual diversity is not a fall from grace, but an expression of the interplay of divine love and human creativity. Revelation is open-ended, unending, intimate, infinite, and relational.

Spirituality. The Sufi mystic Rumi delights in the affirmation that there are a hundred ways to kneel and kiss the ground, and so should we… as we embrace the wondrous, pluralism, multiplicity of divine revelations. Throughout the ages, mystics, East and West, have looked beyond the parochialism of their faith traditions to see God in all things and all things in God. Yet, nothing could be further than the beliefs of the orthodox Baptists who taught me the Bible. Although my father was far from being a fundamentalist, many of my Sunday School teachers proclaimed:

The B-I-B-L-E, O that’s the book from me I stand alone on the word of God

The B-I-B-L-E.

Their Bible described a righteous, line-drawing God, whose salvation was limited, and whose vision of history was backward looking rather than forward moving. Fixed on the unchanging written word of God, conservative Christians, and orthodox members of all faiths, have always been suspicious of mysticism and universalism. Contemplative practices, even Christian meditation and centering prayer, have been seen by biblical literalists and Conservative Christians as a way to circumvent the scriptures and the parochial Jesus they preached.

In contrast, open and relational spirituality, sees religious experiences as personal and open-spirited. We are all mystics. God touches all of us. God is still speaking in every culture, and God’s voice is personal, individual, and global. There is no official monopolistic path to God nor are their official conduits to salvation. While sacraments and scriptures are important and illuminating ways to experience God, all places are “thin places” revelatory of God’s grace and God ratifies scores of spiritual paths to the divine, from praying scriptures, centering prayer, and lectio divina, to Reiki healing touch, visualizations, affirmation, and even the use of spiritually guided psychedelics. Revelation is an open door to divinity, available to a child with five loaves and two fish, a woman caught in adultery, a hated tax collector, or a pious monastic or yogi.[3]

Justice. An open and relational universe and its life-giving Creative Wisdom prizes the gifts of creativity and pluralism. God is alive and still speaking. The world in its diversity is the incarnation of loving wisdom and the goal of life is maximal creativity and freedom congruent with the common community and planetary good. With Alfred North Whitehead, the ethical impulse in a relational universe is to move from self-interest to world loyalty, and to be open and relational in our interpersonal and institutional relationships. To find peace in losing the isolated ego and finding the universal self.

Contemplative activist Howard Thurman asserts that the mystic is inspired by their encounter with God to break down the walls that prevent persons from realizing their full humanity. The mystic challenges injustice in its many institutional forms, while seeking prophetic healing that includes the creative transformation of the oppressor as well as the oppressed. The future is open for oppressor and oppressed alike, and both find wholeness in discovering and living out the reality of God’s presence in their lives as freely, creatively, and justly as possible.

Ministry and Ecclesiology. The doctrine of divine omnipotence leads to cosmic authoritarianism in both theory and practice. God determines all things, and even if we posit human freedom as compatible with divine all-encompassing omniscience and ordination of events, anyone who colors outside the lines is subject to punishment by God and God’s institutional agents. Authoritarian, closed system, and binary visions of God promote patriarchal and hierarchical decision-making within religious institutions. What God has ordained must not be challenged. God’s rules must not be amended. Natural law is strict, unbending, and backward looking, and promotes inflexible judgments related to morality and identity. Backward looking and unchanging natural law undergirds empire in church and state, and the denunciation of otherness, and joins state with church to ostracize unbelievers and outsiders. There is one natural way, unchanging, and obligatory for all persons.

In contrast, the open and relational church and its theological orientations leans toward the future, nurtures creativity and questioning, welcomes creative transformation, and sees institutional and constitutional leadership as universal and evolving rather than restricted to a select group with unchanging and unchallenged doctrines and rules. Natural law evolves and changes, reflecting the ongoing creativity of Divine Wisdom.

Open and relational ecclesiology inspires the embodiment of the spirit of Pentecost and the body of Christ, described in I Corinthians 12, a democracy of revelation and giftedness in which the experiences and vocations of every member matters, and institutional mission and well-being is grounded in exploration and realization of every members’ gifts. Although their vocations may differ, children and laypersons, monks, pastors, and priests, are all inspired and able to share the gospel.

Open and relational congregations aspire to be beloved communities, each recognizing its unique gifts and open to the gifts of other religious communities. Diversity is a blessing and growth an aspiration. As a contemporary hymn proclaims, “God of change and glory, God of time and place, when we fear the future, give to us your grace…For the giver and the gift, praise, praise, praise.”

Evangelism. Open and relational spirituality inspires giving and receiving the good news of God’s grace and quest for creative transformation. John Cobb asks the question, “Can Christ be God news?” and open and relational spiritualities proclaim a resounding, “yes.” The good news that Christians share is inspired by God’s amazing and universal grace. Our good news is that Jesus saves, but not in a binary way. Jesus awakens our solidarity with the earth and its peoples, invites us to open-spirited hospitality, and sees the religious journey as involving listening as well as sharing. Our good news is that God’s circle has no circumference, and God’s center is everywhere. We can honor our truth, rejoice in the faith we affirm, and open ourselves to God’s inspiration in other spiritual centers.

Citing the title of one of my books, the Elephant is running. The Elephant is also loving. The Divine is running and loving. Healthy religion is growing in dialogue and learning. Neither God nor the path to God is complete. God leans toward the future, and open and relational theology does as well. God is faithful and God’s mercies are new every morning. God is alive, and constantly creating, aiming toward the incarnation of love and beauty in our world. Following God, we look toward the horizons of faith, giving and taking, sharing as it is welcome, and learning every step of the way. Trusting God’s grace, we rejoice in the incompleteness of our faith, and recognize that our fallibility and limitation give birth both to the realm of possibility and inspiration to grow. And so filled with wonder, love, and grace, we rejoice in the flowing fountain of God’s love.

How can we keep from singing!

How can we keep from dancing!

` How can we keep from loving!

[1] Found in James Weldon Johnson’s God’s Trombones.

[2] For more on religious pluralism, see my The Elephant is Running: Process and Open and Relational Theology and Religious Pluralism (SacraSage, 2022).

[3] For books on mysticism, Bruce Epperly, The Mystic in You: Discovering a God-filled Universe; Mystics in Action: Twelve Saints for Today; and Prophetic Healing: Howard Thurman’s Vision of Contemplative Activism.